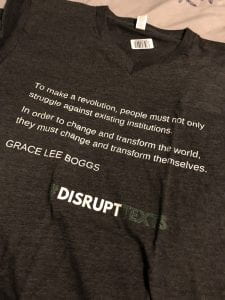

“To make a revolution, people must not only struggle against existing institutions. In order to change and transform the world, they must change and transform themselves.”

Honestly, I wasn’t looking forward to NCTE this year. In the past, NCTE has been a complicated space for me, one that is as exhausting as it can be exhilarating, and one that is always overwhelming. I came in with a lot of things that I had to get done: on the plane, during the conference, on the way home. Always all the things, right?

In the weeks approaching this NCTE, I have had a lot going on, and my mom’s birthday (she would have been 81 this year) came on Saturday, my busiest conference day. There is always a tension in complicated grief on birthdays and anniversaries, so I wasn’t sure how it would all go.

But, it was probably the most beautiful and affirming conference experiences that I’ve had in a long time, maybe ever.

And it was because I showed up for myself.

I have spent my entire life showing up for others: my mother, friends, colleagues, my children, students. I love these people, don’t get me wrong. It is an HONOR to show up in love, solidarity, affirmation, coalition, for others.

But in showing up for others, I often forget to listen to myself and what I want or need, relegating those thoughts to the shameful realm of selfishness.

This NCTE something strange happened.

I just focused on being present. I focused on what I needed in any given moment. I focused on healing parts of me that I’ve been working towards embracing and understanding for the last couple of years: my identity as an Asian American woman.

I went to Asian American (and women of color) author sessions; I facilitated an Asian American teacher panel; I co-presented with my friend Jung about our research on Asian American teachers; we co-facilitated the Asian American caucus open forum and first ever networking event, and I met a lot of amazing authors.

I didn’t push myself to hang out with all of the amazing people I love at NCTE. If I saw them, we hugged and talked. If I didn’t, I wasn’t running around frantically to make things happen (well, except for when I was running frantically after the teacher panel to Debbi Michiko Florence’s signing that was already over, insert sad emoji here). I connected with people I didn’t know, but now consider friends. I met people who I’d only ever seen on Twitter. I spent quality time with people I deeply cherish.

I was present.

I showed up.

I showed up for myself.

I showed up for the little girl who loved to read, who loved the windows into the worlds of others.

I showed up for the teenager who had just lost her mom, and who desperately needed to be seen and understood.

I showed up for the young mother who felt so overwhelmed that she just wanted to become invisible.

I showed up for the Asian American associate professor who is trying to embrace all of who she is, so she can show up stronger for herself and others.

I showed up for the author inside of me, who sees the calling and knows she has a voice and a story to tell.

And you know? Even though there are still all the things to do, I am letting go of some of them, to make room for the best people and the best things, the affirming things, the enriching things, the nourishing things.

So, I am not bummed if I missed you at NCTE. I am not sorry.

When our paths cross next, I will be more present with you because I am transforming. When I show up for you next, I will show up with more of myself because showing up will be borne of love and choice and not obligation and inadequacy. I will know what I am bringing to you through knowing who I am.

Much love to all of you who I did connect with at NCTE, whether for a super brief selfie of appreciation and love or a 5-minute conversation or over food, in sessions — however it was, thank you. I am grateful for your contribution to me, for the restoration of being fully present.

I’ll see you all when I see you all next. In love and with gratitude.